In 1988 while most Queenslanders were busy celebrating the bicentenary and hosting the World Expo 88, the government was fighting a bitter campaign to stop the Daintree Rainforest being heritage listed and was desperately trying to distance itself from the corruption that flourished under Joh Bjelke-Petersen’s government, newly released cabinet papers reveal.

The documents show the state government, led by premier Mike Ahern, resented Canberra’s moves to create the Wet Tropics World Heritage Area in the far north.

Then Labor prime minister Bob Hawke wrote to the state government requesting its support.

“There is no doubt the wet tropics is an outstanding natural asset and listing it would be potentially of enormous benefit to Queensland,” Hawke urged.

However the call fell on deaf ears and the papers reveal a great deal of cabinet time went into opposing the listing. Queensland government ministers even travelling to Brazil to fight the move.

The fight against corruption

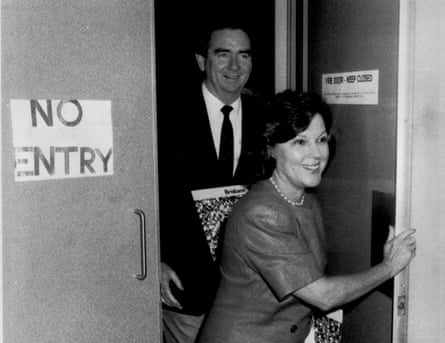

When Ahern took the premiership in December 1987, trust in state institutions was at an all-time low.

Government and police corruption had been allowed to flourish under the leadership of Joh Bjelke-Petersen for the prior 19 years.

But with the Fitzgerald inquiry into possible police corruption in full swing, Ahern knew Queenslanders would no longer cop it. He dedicated 1988 to cleaning up institutions and made more than 2,000 decisions in that vein, cabinet documents made publicly available on Tuesday reveal.

One was the introduction of the Public Accounts Committee, another took the Police Complaints Tribunal out of the Police department, which paved the way for the Crime and Corruption Commission.

Ahern forced ministers to table their expenditures publicly, which would lead to three of his ministers being jailed for misappropriation.

He prevented corrupt police commissioner Terry Lewis from retiring and collecting his superannuation, or getting another job.

Then Ahern convinced his cabinet to expand the Fitzgerald inquiry’s terms of reference beyond the realm of police, something he regards as “one of the most important decisions made in Queensland in recent times”.

“Tony Fitzgerald came to me and said this started as a police inquiry, and now a number of key players who are clearly involved in corruption are telling us that they won’t appear because they’re not policemen,” he told journalists.

“So he said: ‘I want you to give me broader terms of reference.’

“I knew how difficult that would be to get through the cabinet and the party machine groaning through all this, so I decided to take it to cabinet as the lone ranger.

“I said [to cabinet] you can either do this and get it done, or you can leave it for a month and let the press kick us around for a month and then do it.”

Lawyer Anthony Marinac, who has spend the past year collating the cabinet minutes, said the documents showed why Ahern’s time as premier should be remembered positively.

Ahern chose to reform despite the temptation to simply be a “son of Joh” backed by his conservative cabinet.

“During the Bjelke-Petersen era, it was individuals making decisions. So if you could contact someone in power they could make decisions in your favour,” Marinac said.

“One of the biggest sea changes that came with the Ahern government was the idea that institutions and processes matter.”

Ahern was deposed by his own party two months before the 1989 state election, which the Nationals lost resoundingly to Labor’s Wayne Goss.

Climate change awareness

Despite the government’s opposition to the heritage listing of the Daintree, Ahern did recognise the impacts of climate change by banning the use of CFCs and establishing a greenhouse gas policy.

Ahern admitted it was a “substantial issue” and raised the levels of canal walls in developments across the state.

“Developers complained at the time but I did that in recognition of the rising sea levels, which were threatening at that time,” Ahern reflected. “So these people today who are deniers of all of this, they are wrong.

“The sea levels have risen now and it’s not much in the history of the world but it’s enough to tell us that it’s time to make some changes.”

Marinac described the Ahern government’s stance on climate change as “surprisingly progressive”.

“I came away from those documents very frustrated, thinking what have we been doing for the last three decades, if we were here in 1988, and we haven’t progressed in 2018,” Marinac said.