The message came over the radio and was relayed into the engine room of the Cheynes IV whale chaser, where engineer Bob Reeby was at work.

“That was it: ‘Home speed, we’re going home’. That was the end of an era. It was a pretty sad moment,” Reeby recalls.

At 25, Reeby, then a young father, had been working for Cheynes Beach Whaling Company (CBWC) since joining as a deckhand at 16. But he knew what it meant for some of the older men. “They were too old to go on the fishing boats.”

That call to return to port on 21 November 1978 marked the end of commercial whaling in Albany, Western Australia, and, with it, the end of commercial whaling in Australia.

No whales were caught that day. The Cheynes IV skipper and harpooner Axel Christensen was the man to kill the final whale the day before – the explosion of gunpowder propelling the grenade-tip into the chest of a sperm whale.

Cheyne Beach Whaling Company whaler Axel Christensen, left, was the last man to kill a whale in Australian waters. Also pictured is Gordon Cruickshank.

From its opening in 1949 until 1978, CBWC killed 14,878 whales. As a major employer, the closure had a devastating effect on the town and the families who were suddenly without income.

“Albany took a hell of a hit,” Reeby says. “It was a job and it was accepted back then. I don’t regret it. It was part of Albany’s history.

“But yes – attitudes change. If whaling was going on here now, then I’d probably be campaigning against it.”

The Australian author Tim Winton, patron of the Australian Marine Conservation Society, grew up in Albany. He doesn’t remember seeing any live whales in the ocean as a child but he saw plenty of dead ones.

When visitors came from the city, the Winton family would head to the station’s observation platform for a view of the flensing deck – the place where the skin and blubber was manually stripped off the whales.

“You would stand there in this fug of blubber steam – the most repulsive smell you could imagine. At some level, it was a crude form of entertainment.

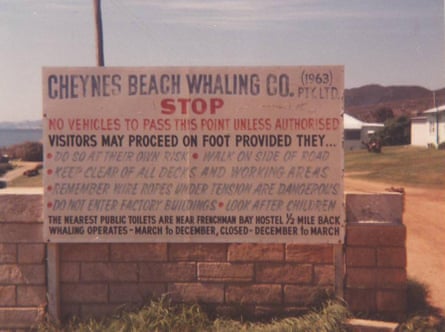

Clockwise from top: The entry sign for Cheyne Beach Whaling Company in 1978, manning the harpoon, pieces of sperm whale at the whaling station in 1977 and the flensing of a sperm whale in 1960.

“They’d winch up the sperm whales and they had this steam-driven circular saw to saw the heads off. I was a country boy so for me it was normal, but you’d take people there and they would be gagging watching all of this – it was high entertainment. But as I got older and maybe taking cues from the city folk, that kind of … pleasure … well, it wore off.”

By the time Winton was 16, he understood whaling wasn’t only “an unpleasant looking business” but was “unnecessary”.

One 13-metre whale could yield seven tonnes of oil. Meat and bones were dried and used a fertiliser – the original “blood and bone”. But cheap crude oil and synthetics were pricing it out. Whaling was becoming uneconomical.

“To top it all off, my townsfolk were helping hunt sperm whales to the point of local extinction,” Winton says.

Changing a nation

The late 1970s were pivotal in Australia’s shift from a nation with a century and a half of lawful whaling history.

In 1977, CBWC was already the country’s last commercial whaling operation when a group of Sydney-based anti-whaling activists arrived in a beaten old truck with two inflatable boats.

The idea was to convince the townsfolk the future was in watching whales, not killing them. But they would also take their boats out during the hunts to get between the chasers and their quarry.

“I remember when the activists came out, yes,” Reeby says. “I didn’t like them but I had the upmost respect for them.”

Names that have attained legendary status among whale conservationists for that Albany trip include Jonny Lewis, Bob Hunter, Tom Barber and Frenchman Jean-Paul Fortum-Gouin. American tourist Aline Chaney was also among them. She married Barber and they were together for more than 40 years until Tom died earlier this year.

“Most people on the east coast didn’t even realise there was still this station in Albany and nobody really thought about going over there to confront them,” Aline Chaney Barber, 72, says. “When we got there, nobody would rent to us.”

They ended up in a freezing shack on a beach with no running water.

“At the start people weren’t that pleasant but as time went on we got to hang out longer in the pub there, and we could bring our points across,” she says. “Jonny Lewis and Tom were going out in these Zodiac boats in the ocean in winter, way out to sea. Tom had his captain’s licence but, when I think back now, it was sheer madness. But when you’re young, you’re immortal.”

A whale chase in Australian waters.

In Sydney, a volunteer-run group called Project Jonah had formed a few years earlier. Pam Eiser has been volunteering with the group since 1976 – she’s now the president.

“We had three aims,” says Eiser, now 63. “We wanted to prohibit whaling in Australia and then ban the import into Australia of any whales or whale products, and then work towards an international ban on whaling. We are still waiting for the third one to be achieved but some of us have got a lot of patience.”

Eiser has attended every meeting of the International Whaling Commission meeting since 1990 (she missed this year’s in Brazil through ill health) and has been part of the Australian government’s delegation several times – a role which, she points out, has to be self-funded.

“There’s a story that prime minister Malcolm Fraser’s daughter Phoebe approached her dad and said she wanted whaling to stop. Well, we certainly provided her with pin badges and things like that.”

Through public pressure, Fraser sought a meeting with Project Jonah and asked that if he agreed to fund a public inquiry, whether they would accept the outcome.

Securing the whale catch in late 1970s.

In March 1978, Fraser – who showed his own hand by admitting he found whaling abhorrent – announced Sir Sydney Frost would conduct an inquiry into whales and whaling.

In 1980 the Fraser government accepted the inquiry’s recommendations, repealed the Whaling Act that saw whales as a commodity, and introduced the Whale Protection Act. Australia would also pursue a global ban through the International Whaling Commission.

Sydney businessman Richard Jones was one of those who picked up a Project Jonah leaflet in 1977 and took on the cause, travelling to International Whaling Commission meetings as an activist. He also took on Fraser’s advisers.

At one point he paid to have a life-size blow-up whale made with the words “Save the Whales” printed on the side in English, but also in Japanese and Russian, that travelled around the country. He also took out Project Jonah adverts in newspapers asking for donations.

But perhaps his most notorious contribution was at the IWC meeting in England in 1978.

“The day before, I went to a local abattoir with two one-litre grapefruit juice bottles and had them filled with cow’s blood,” Jones recalls. At the meeting the following day, Jones says, he joined activists who “filed in peacefully to unfurl some banners” but he made sure he was the last one to leave.

“I poured one of the bottles out all over the working papers of the Japanese delegation. All hell broke loose – I was called a terrorist by the Japanese.”

Jones, now 78, was one of the founders of Greenpeace Australia and was a New South Wales MP for 15 years, first as an Australian Democrat and later as an independent.

The anniversary

Albany’s Historic Whaling Station is not letting the 40th anniversary go unmarked. It will host a music and visual arts performance. The old whale oil drums and the processing factory that held the cookers will be filled with whale song and artistic reflection.

“We try and just tell the story here of what happened – it was people’s livelihood,” the site’s general manager, Elise van Gorp, says. On Wednesday, some old whalers and their families will have a morning tea.

Now retired, Bob Reeby volunteers at the whaling station once a week. He points tourists to a sign that says more whales are shot in Albany these days than when the station was open.

“But now, all the whales are shot with cameras,” he says.

Winton has met former whalers, and talks about their capacity to change with the times, and to be gracious. A character in his second novel – Shallows – was based on one of the activists, Jonny Lewis.

A Greenpeace inflatable tries to hinder the shooting and eventual transfer of a minke whale by a Japanese whaling ship in the southern ocean in December 2005.

“It’s strange that this happened inside my own lifetime, something that was normal and seemed like forever and eternal – that couldn’t be undone – has become a cultural anathema,” he says.

“There were adults around me growing up who said it would be the end of Albany. I bet some of their sons and daughters will be there tonight at the celebration – some of them will probably be running whale-watching tours.

“The fact is I can go out now and I swim with whales but that was impossible 20 years ago not just because I lacked the means, but also there just were not enough whales in the water.

“In that sense as we stand now around all this decline and diminution in the world, there’s this beacon of success and of cultural change that we need to remind ourselves of.”