How do you move an electric ferry built for 100 nautical mile sprints across the Pacific? On another, much bigger, boat of course.

What will be the world’s biggest electric ferry will start ocean trials near Hobart in May, before being delivered to its new home in Argentina around the end of the year.

But where LNG-powered ferries can be loaded up with fuel cells, it’s a different story for a vessel built for trips up to 100 nautical miles, says Stephen Casey, the CEO of family-owned Tasmanian company Incat – one of the major ferry makers in the world.

“I think the preferred way is a heavy lift ship,” he told The Driven this week in an interview.

Incat stepped into the electric market during the COVID pandemic. Its South American client ferry operator Buquebus had to pause an order as passenger numbers collapsed, and the delay gave both companies an opportunity to experiment.

“The decision was kind of forced upon us. We had started to design and build this vessel as an LNG-powered vessel then COVID1 hit. Buquebus was pretty much shut down overnight,” Casey says.

“We had some time to innovate. We considered a hybrid, which is a lower risk option when considering port infrastructure and ability to recharge, but in this case Buquebus have control of their own ferry terminals in Argentina and Uruguay so they could build their own [charging] infrastructure.”

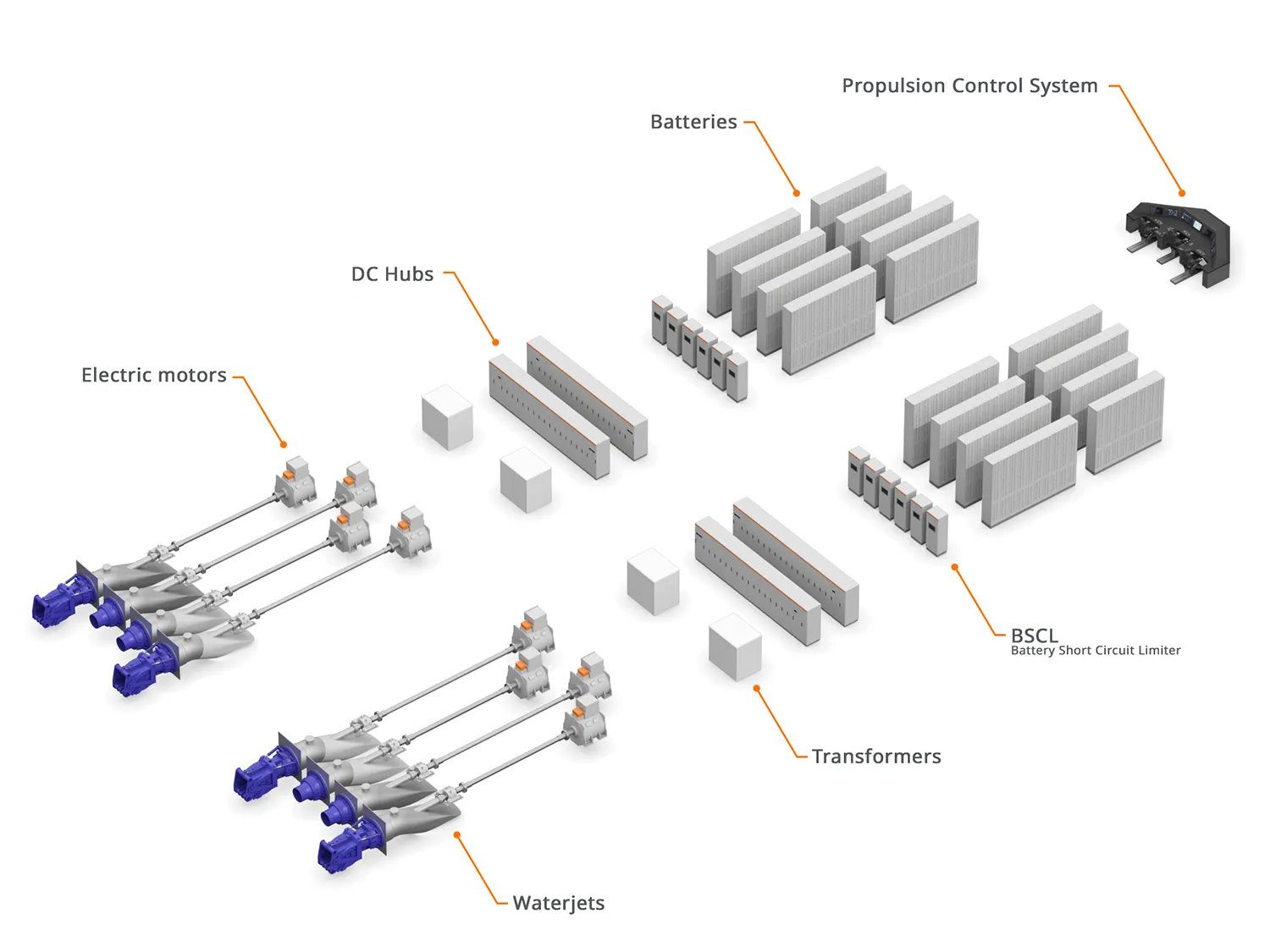

The outcome was the Hull 096, a vessel that met Incat’s lightweight, fast requirements but swapped out an LNG engine for a 250 tonne lithium-ion battery system.

“Moving to a more electrified vessel… we still have the benefit of being lightweight which means we draw less power to move,” he says.

The main challenge was sticking to the company’s own design vision of delivering high speeds and low weight: They needed the right battery, switchboards, motors and cables in order to get a like-for-like swap in terms of weight.

In the end, Incat managed to build a slightly lighter ferry with a 40 megawatt hour (MWh) battery system than the original LNG engine.

It will be launched in May and undergo final testing and a fit out that will include a whole floor devoted to a duty free shop, before being shipped to South America around the end of the year.

And while Incat has just built a ferry with the biggest ever battery system, the biggest ferry – by deck space – is a Turkish-made vessel ferrying passengers along the Norwegian coastline.

The Hull 096 is 78 metres long but can travel at up to 27 knots with a maximum of 2100 passengers and 225 cars.

The Bastø Electric is 145m long, but with a 4.3 MWh battery can ferry just 600 passengers and 200 cars around Norway’s fjords.

Ports needs to be ready

The market for fully electric ferries is emerging slowly, mainly in Europe where there are incentives to decarbonise and penalties for those who don’t.

Denmark in particular passed laws this year that will charge a carbon tax on vessels plying its waters, with the tax to be phased in over the next five years.

The difficulty for ferry operators wanting to switch to electric is of course, power supplies in ports.

“The consistent constraint we have to be able to deal with is the power supply to ports, so vessel operators know they have a reliable recharge in the port,” Casey says.

European ports are installing charging infrastructure and some operators are setting up their own battery backup for electric vessels.

Some 35 per cent of trans-European core ports are equipped with shore-side electricity supply, for a total of 407 berths, according to the European Environmental Agency.

But that also means the market for risk averse buyers is still for hybrids.

This is where Incat is focusing its attention next, but while making it possible in future to easily swap out the LNG engine for a battery motor.

It is currently designing a hybrid electric ferry for Danish company DFDS.

Rachel Williamson is a science and business journalist, who focuses on climate change-related health and environmental issues.