The year is still young, yet it’s already easy to feel drowned in a sea of new book recommendations. While some readers have been diving headfirst into trendy divorce memoirs — or the latest dragon smut (no judgment!) — a wave of deeply personal and thought-provoking releases has made it to bookshelves. The best new nonfiction we’ve read this year explores trauma, the color blue, the devastating shortcomings of western media, and a lifetime’s worth of love and sex. Meanwhile, a previously published South Korean novel from last year’s Nobel Prize in Literature winner has finally been translated into English, and the author of 2021’s buzziest fiction debut hasn’t missed a step with her follow-up, a confident and imaginative collection. Oh, and March just gave us a vampire story we’re describing as “the closest thing we have to horror’s Moby-Dick.” Narrowing down where to start isn’t easy, but we have some suggestions.

Books are listed by U.S. publishing date with the newest titles up top.

Trauma Plot, by Jamie Hood

Already one of the most rigorous and astute critics working today, Jamie Hood follows up her debut, How to Be a Good Girl, with Trauma Plot, a hybrid of memoir and criticism that deftly excavates how we talk about trauma. She writes about her personal life from an evocative remove, detailing “Jamie’s” experience of trauma, rather than relying entirely on the first person, to reimagine archetypes of sexual violence. At one moment, she articulates her intensifying boredom with an older fling in ruthless, unflappable clarity; the next, she brings the reader inside the lonely humiliation of screaming in public after a groping. Her work recalls other great writers of the self, like Annie Ernaux and Sylvia Plath, and the critical eye Hood brings to the stories we tell about trauma reveals the power and limits of personal narrative. —Isle McElroy

The Buffalo Hunter Hunter, by Stephen Graham Jones

“I am America’s worst nightmare: the Indian who wouldn’t die.” Thus speaks Good Stab, the Blackfeet narrator at the heart of Stephen Graham Jones’s epic novel of blood, vengeance, and genocide. It’s no spoiler to say Good Stab is no ordinary mortal; Jones has written his Interview With the Indigenous Vampire, but The Buffalo Hunter Hunter transcends genre. It may be 1912 when Good Stab tells his life story to a Lutheran minister stationed at a Montana trading post, but the novel roams across centuries, casting a cold eye over the many atrocities of Manifest Destiny. Jones’s askew, hyperconversational prose has never been better suited to its story, and over the first two-thirds of the book he builds the fire that fuels the sheer audacity of the climax. It’s a landmark of horror and historical fiction alike, perhaps the closest thing we have to horror’s Moby-Dick. —Neil McRobert

Stag Dance, by Torrey Peters

Torrey Peters’s second book, Stag Dance, is at once a return to earlier forms and a massive step forward. The book contains three short stories and the titular novel. Peters self-published two of the stories, “Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones” and “The Masker,” years ago, but they’ve lost none of their power or urgency. In the former, a collective of trans women unleashes a virus that puts the entire world in the position of choosing their gender — to make the same choice those in the collective have made. In “The Chaser,” a young man at a boarding school must confront the redoubling consequences of refusing to confess his love for another student. The title novel, Stag Dance, is an engrossing historical tale about turn-of-the-century lumberjacks who hold an annual dance where some of the men choose to attend as women. The protagonist, Babe, never explains or defends his desire to go as a woman — it is simply is what he wants — and this refusal to clarify is a sly, confident vindication of desire and selfhood. Stag Dance is funny, brilliant, and effortlessly original. —I.M.

➼ Read Grace Byron’s review of Stag Dance and Andrea Long Chu’s chat with author Torrey Peters.

Ultramarine, by Mariette Navarro; translated by Eve Hill-Agnes

French playwright Mariette Navarro’s debut novel, Ultramarine, follows the female captain of a cargo ship, the only woman onboard. After allowing her crew to go swimming without her, they return with one more crew member. Though the book makes good use of its claustrophobic, paranoid setting, it is far more than a simple thriller. The novel offers a strange, compelling exploration of how loneliness shapes a person — and might drive them to pursue the comfort of isolation. Navarro is an expert at navigating the surreal, fatalistic way the captain thinks of herself. She always believed she was destined for the sea and accepted this life with a detached self-assurance, but as the novel continues, her sense of identity begins to break down. The self, Navarro reminds us, is often constructed within the meticulously defined routines of our lives, and any change to those is liable to reveal parts one would rather not see. This is a haunting, unpredictable novel that’s hard to shake after reading. —I.M.

The Unworthy, by Agustina Bazterrica

Agustina Bazterrica is not afraid of an extreme dystopia. Her breakout hit, Tender Is the Flesh, posited a world in which cannibalism has become industrialized and meat is quite literally murder. Her follow up novel is both a quieter and more elaborate affair. The Unworthy takes place an indeterminate amount of time after an unspecified global catastrophe. There are hints of nuclear incident, climate collapse, AI run amok — all filtered through the narrow perspective of a survivor’s diary written in a convent where evil nuns hold sway over the worthy and unworthy alike. Bazterrica nods to other texts — the apocalyptic horror of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, the entrenched misogyny of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, the violent erotic charge of Rumer Godden’s Black Narcissus — but she synthesizes it all into something wholly strange, timeless yet frighteningly timely. —N.M.

One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This, by Omar El Akkad

Omar El Akkad’s “breakup letter with the West,” One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This, charts the author’s gradual recognition of the many lies and hypocrisies at the core of western ideals. Though the book largely revolves around spurious media coverage of Israel’s war on Gaza, El Akkad’s great talent is in showing how, over the past few decades, corporate journalism and western powers have undermined our ability to confront global atrocities. He identifies this in near-daily instances of false political engagement, in which newspapers endorse mass-deportation campaigns and U.S. spokespersons express sympathy for the innocent people being slaughtered by American weapons. We live in a time, according to El Akkad, when “ethical double-jointedness [is] a necessary requirement for the daily debasement of modern political life.” One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This is an angry, uncompromising book full of exasperated wisdom and virtue. Its honesty is invigorating. —I.M.

Immemorial, by Lauren Markham

Lauren Markham’s Immemorial is an attempt to name a phenomenon most of us know very well: anticipatory grief for the impending collapse of the natural world. The book reckons honestly with this preemptive loss and the guilt any thinking person may feel for having contributed to the planet’s destruction. Complicity, she writes, “had paradoxically become something of a linguistic escape hatch: simply admit your complicity and then you’d subvert it.” But Markham has no interest in subverting this feeling. Instead, she faces it head-on, writing about the impact of collective memory in both decimating and protecting our ecosystem. The desire to memorialize through statues and buildings is often paired with the impulse to alter the truth, to construct the memories that won’t fracture a community’s sense of its implicit goodness. Markham tries to use her grief as the “raw material for creation.” What results is a vital, moving portrait of how to live in a world we may never get back. —I.M.

Black in Blues: How a Color Tells the Story of My People, by Imani Perry

The latest by Imani Perry, a professor at Harvard and a MacArthur Fellow, is as alluring as it is provocative — she traces the relationship between the color blue and the Black experience in America and throughout the world. Her reach is expansive: In brief, pithy chapters she discusses various intersections between Blackness — as a racial classification and a manner of engaging with the world — and assorted manifestations of blue in geography, music, literature, clothing, and many other categories. She also draws from her own life and her knowledge of history, art, and contemporary culture to create a quilt (an analogy she invokes) in which distinct patterns and sections brush up against and interact with one another. Together, they constitute an entirely new creation, a piece that will prompt you to evaluate Blackness afresh via the color blue and to consider how that color has been a through-line, an inspiration, and a harbinger of oppression for Black people across space and time. —Tope Folarin

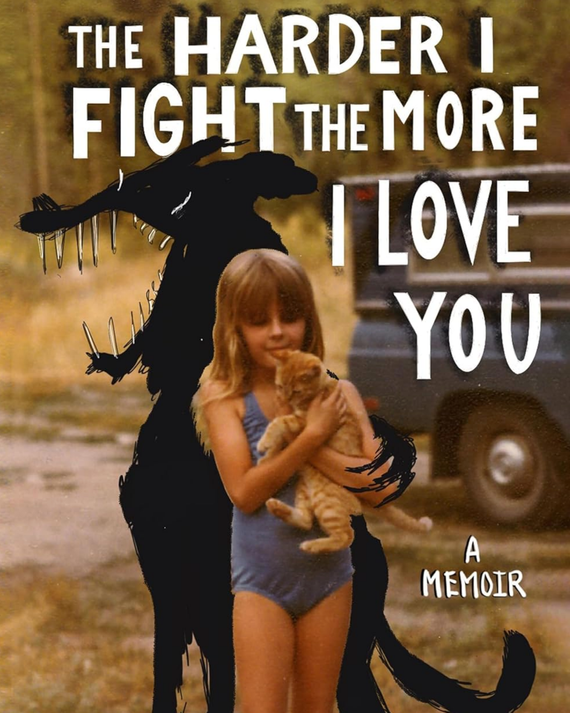

The Harder I Fight the More I Love You, by Neko Case

Indie-rock idol Neko Case, singer of “I Wish I Was the Moon” and front woman of the New Pornographers, has hinted in songs at the turmoil she experienced in her childhood, but her lyrics are far more oblique than this memoir. Born to teenage parents who were “poor as empty acorns,” Neko was largely left to her own devices — especially after her mother seemingly faked her own death only to reappear a year later with barely an explanation. The book is full of fairy-tale details: Adults are mostly threatening or absent, children are in perpetual danger, and nature offers moments of transcendence and almost mythological meaning, as when a pair of horses walks past Neko’s house as though she’d summoned them. Later, the Pacific Northwest punk scene and a necessary break from her mother open up a true escape route. You can feel her elation on the page. —Emma Alpern

➼ Read Emma Alpern’s review of The Harder I Fight the More I Love You.

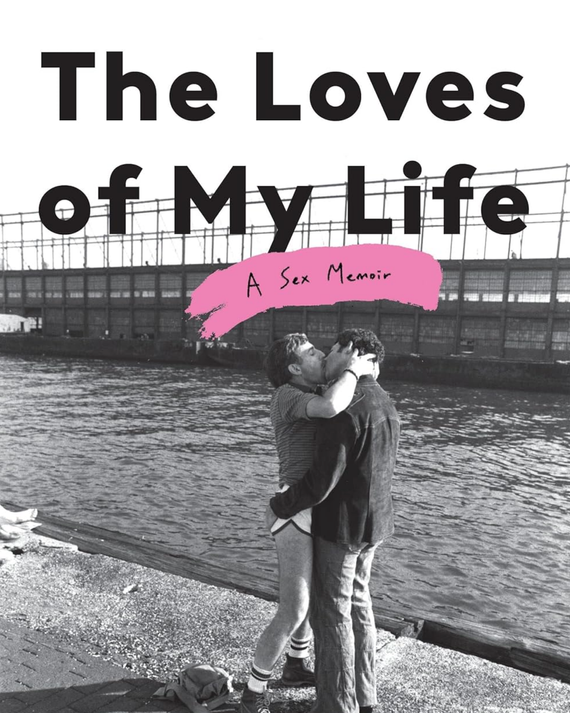

The Loves of My Life: A Sex Memoir, by Edmund White

At 85 and “a practicing gay since age 13,” the novelist Edmund White lived through the furtive 1950s, when being gay was a crime; the brief, exuberant post-Stonewall years; and the decade when AIDS tore through his community of friends and lovers. But this outline is far more serious than White’s joking and explicit memoir, in which pleasure is always the goal. “I’m at an age when writers are supposed to say finally what mattered most to them,” he writes. “For me it would be thousands of sex partners.” They range from acquaintances to roommates to husbands; there are hookups with dads in station wagons, paid-for sex in rent-by-the-hour hotel rooms, and “nocturnal encounters” in the Colosseum back when Rome kept it open to the public. It’s all sexy, funny, and romantic, too: “Sex was always linked to love, even during so-called anonymous sex. I fell in love ten times a day.” —E.A.

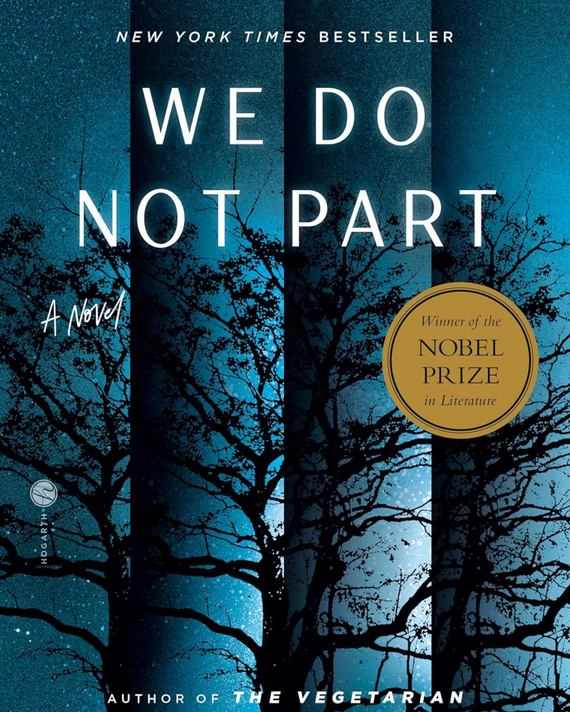

We Do Not Part, by Han Kang; translated by e. yaewon and Paige Aniyah Morris

In a small apartment in Seoul, a historian named Kyungha lives in near-total isolation, wracked by chronic pain. A friend asks her to travel to Jeju Island to rescue a pet bird, and her snowy journey puts her into mysterious contact with the past. The island was the site of an uprising in the late 1940s, one that was brutally suppressed by the anticommunist Korean government with the apparent support of occupying American forces; tens of thousands of people were killed. Han, who won the Nobel Prize in Literature last year, has written about the Jeju uprising before in the brutal and lucid 2014 novel Human Acts. Published in South Korea in 2021, We Do Not Part is both an elaboration on that book’s ideas and something wholly its own, a chilling look at generational memory and the lifespan of atrocity. —E.A.

➼ Read Robert Rubsam’s review of We Do Not Part.

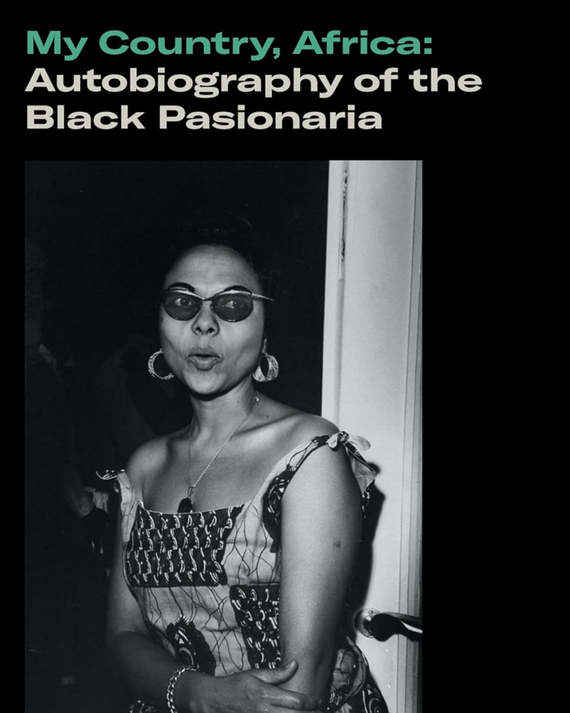

My Country, Africa: Autobiography of the Black Pasionaria, by Andrée Blouin

In their foreword to this book, writers Adom Getachew and Thomas Meaney list a few sobriquets by which Andrée Blouin was known during her life, including “Africa’s Woman of Mystery” and “the Most Dangerous Woman in Africa.” While these monikers may capture her notoriety, they don’t come close to conveying the impact of her work and presence. Throughout her astutely observed and utterly captivating autobiography, which was originally published in 1983, Blouin charts her harrowing youth and extensive engagement with various African leaders and independence movements during the mid-20th century. Among other activities, she advised major postcolonial leaders in Algeria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ghana, Guinea, and Mali, and was present for several key moments in African political history. One is tempted to invoke the typical cultural emblems of ubiquity in describing her influence and accomplishments — she could be characterized as the Zelig or Forrest Gump of Africa — but considering she was a real person who participated in real events, perhaps we should replace their names with hers. —T.F.

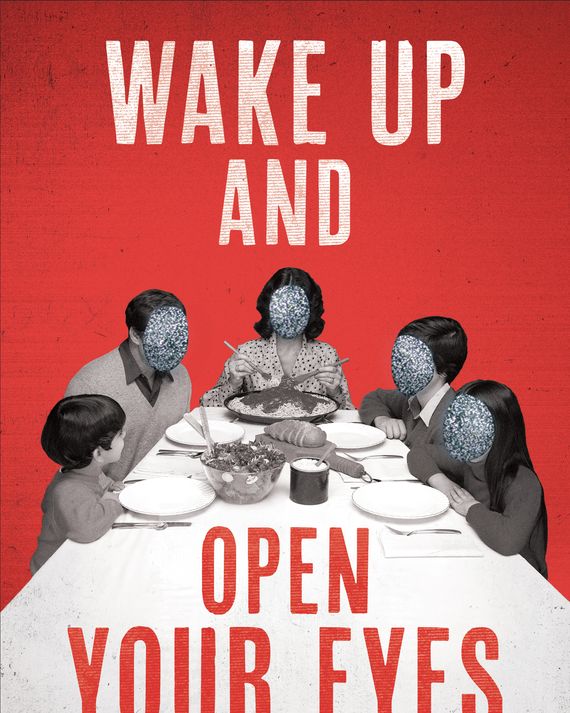

Wake Up and Open Your Eyes, by Clay McLeod Chapman

Clay McLeod Chapman has written some of the most ballsy, go-for-the-throat horror of recent years, but in Wake Up and Open Your Eyes he digs a scalpel point into the exposed nerves of Trump’s America. The nation falls to a mass epidemic of demonic possession spread through the viral messaging of right-wing media. Worried about his parents’ well-being, Noah ventures out of his liberal Brooklyn echo chamber to travel home to Virginia. What he finds there is vicious, disgusting, and tinted with void-black humor, but Chapman is as adept at the slow burn as he is at the Grand Guignol. The book’s long middle section detailing the incremental corruption of Noah’s family is as chilling and oppressive as contemporary horror comes. Chapman pulls not a single punch in taboo, nor does he soften his blows in an attempt at moral relativism. The result is an apocalyptic allegory for our digitally siloed reality. —N.M.