hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Seoul travels] Insadong: At the crossroads of tradition and change

The original version by Édith Piaf is fine, and the cover by Louis Armstrong is pretty good, but the performance by the 12 Cellists of the Berlin Philharmonic is the best way to listen to “La Vie en Rose” in the fall. The autumn is pretty much the only season when one can appreciate the subtle presentation of the rose’s red-hot passion, muted by the sobriety of the cellos and the distinctive restraint of the Berlin Philharmonic.

While listening to the song, I take out a volume of poetry by Rainer Maria Rilke. While Rilke is renowned as the “poet of roses,” he was as likely to compare life’s ripeness to wine as to roses. That’s what we find in the poem “Autumn Day,” which begins with the lines, “It is time, Lord. Summer was grand.”

“Let the late harvest linger. / Give it two more southern days. / Make it full and bring her / final sweetness into those heavy vines.”

As the poet says, October is the final month when the sun shines down with kindness before we move toward winter. That precious sunshine warms my shoulders as I head to the Insadong neighborhood in downtown Seoul. This was one of the city’s first areas to block off its main street for pedestrian traffic on the weekends. I’m there to sample the tea for which the neighborhood is known.

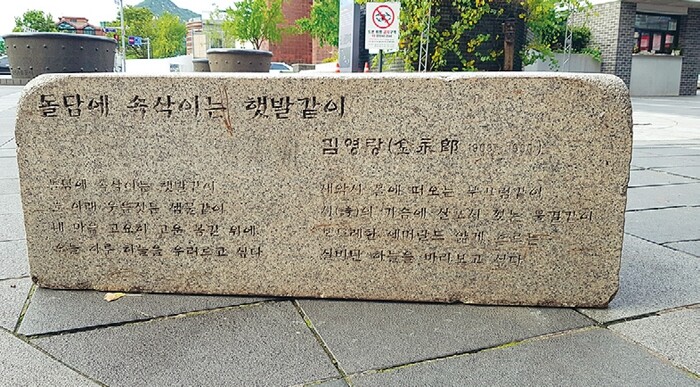

Emerging from Exit No. 6 of Anguk Station on the Seoul subway, I walk toward Anguk Neighborhood Intersection, where I find a little plaza called North Insadong Madang. The plaza used to host colorful events every day, but since the coronavirus pandemic began, the plaza’s big statue of a calligraphy brush and a sign that says, “Insadong: home of traditional art in Korea” look rather lonesome. A stone block nearby is inscribed with the poem “Sunbeams Whispering on the Stone Wall,” but I have to strain my eyes to make out the words.

Insadong is a street for the poets and the artists. If Yeouido was once dominated by the digital culture of broadcasters and videos, Insadong is filled with the analog culture of newspapers, writing, and painting. The neighborhood inevitably comes up in any discussion of the humanities (in East Asia, this particularly means the disciplines of literature, history, and philosophy) in Seoul. The name “Insadong” takes the syllable “in” from Gwaninbang and “sa” from Daesadong, the administrative districts to which it belonged in the early Joseon Period and after the Gabo Reform of 1894, respectively, while “dong” is the Korean word for “neighborhood.”

As the home of a government office called Dohwawon (Bureau of Painting), Insadong perhaps inevitably attracted vendors of painting and writing implements. Some shops here specialized in old books, while others catered to calligraphers, selling the “four treasures of the study”: brush, ink, paper, and ink stone. This is where impoverished aristocrats sold off ancient texts to support their lifestyles. After the aristocracy was brought low by the collapse of the Joseon Dynasty, their old furniture was put on sale in antique stores in the neighborhood.

About a minute’s walk down Insadong Street from North Insadong Yard, I come to Korea’s oldest antiquarian bookshop on the right-hand side. The store has been run by three generations of the same family since it was founded in 1934 under the name Geumhakdang; it was given its current name, Tongmungwan, in 1945.

A little further south along the street toward Jongno 3-ga, there’s an alley on the left called Insadong 14-gil. The alley contains some of the neighborhood’s best-known dining establishments. Places such as Auntie’s House, Sacheon, and Seoncheon have long catered to the tastes of Seoul’s writers and artists.

Before I was hired at a broadcaster, I was briefly employed at a magazine and newspaper, so I remember the charm of the side streets of Insadong in their heyday. In this alley in particular, the clientele included intellectuals and artists as diverse as the dishes on offer, such as ganjang gejang (raw crab marinated in soy sauce), nakji bokeum (spicy stir-fried octopus), yeonpotang (beef and radish soup), and samhap (a combo of three dishes, often kimchi, pork, and skate).

In the middle of this alley is a restaurant featuring food from Korea’s southern region called Yeojaman. This is the old name for Suncheon Bay, but it also serves as a pun meaning “only women.” A sign at the restaurant says, “Conservation here should focus on women, with no mention of religion, politics, or the army.” On the other side of the street is the teahouse “Gwicheon,” meaning “return to heaven.” That’s the title of a beloved poem by Cheon Sang-byeong, who used to run this teahouse.

“On the day the beautiful picnic of this life comes to an end / I will go and say it was beautiful.” The poet whose imagination was rich enough to compare life to a brief picnic wrapped up his own picnic long ago and departed for the next life. But his teahouse and his poetry remain, which the city of Seoul has recognized by putting up a placard about the café being a “legacy for the future.”

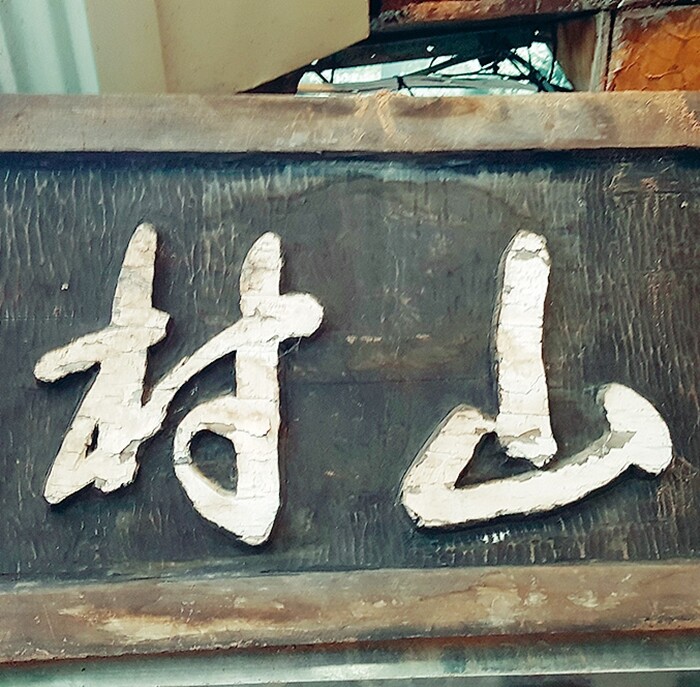

Of the various people I met in Insadong, the one I’ll never forget was the monk Beopjeong. After his book came out, he treated the entire editorial board to a meal at Sanchon, an Insadong restaurant specializing in temple food. I’d only recently completed my military service, and my hair had yet to recover from the army-issue buzz cut. Even so, I had the honor to sit at the feet of the leading lights of literature and observe their greatness from up close. That was the day when I realized that someday I wanted to make my living as a writer and to live immersed in the written word.

I emerge back onto the main street at Insadong. Big shopping centers such as “Anyoung Insadong” and “Ssamziegil” are the new face of Insadong. These contemporary structures house a variety of interesting sights and shops. As I walk past Sudo Pharmacy, which has long been a rendezvous point for people meeting up in Insadong, I spot art galleries, picture framing stores, and shops featuring arts and crafts. There’s also a kebab shop, an Indian restaurant, and a place serving up a cotton candy-style confection known as kkul-tarae, literally “honey coils.”

Many are worried that the flood of commercialism is eroding Insadong’s distinctive identity. They think the neighborhood needs to focus on its authentic appeal, rather than knock-off imitations. But plenty of others point out that the neighborhood has to have some big draws if it’s to remain sustainable and call for a bold embrace of change, along with tradition. It’s a confusing time for a neighborhood that needs to draw tourists into the warp and woof of time and space.

At the entrance to an alley, a foreign musician is playing the violin alone. I’m reminded of what Bak Ji-won pondered as he leaned on a railing at a pavilion in Beijing’s Liulichang Street (a neighborhood with a similar vibe to Insadong) back in 1780.

“Ah! If there were only one person in the world who could truly understand me, I would have no regrets,” said Bak, an influential thinker in the late Joseon Dynasty.

Bak was speaking about the loneliness that comes from not being appreciated by the world. The artists I met in Insadong feel today as Bak felt back then.

By Son Kwan-seung, travel writer

Edited by Seoul& editorial board

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0416/8917132552387962.jpg) [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

[Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces![[Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0416/8317132536568958.jpg) [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

[Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

- [Editorial] Koreans sent a loud and clear message to Yoon

- [Column] In Korea’s midterm elections, it’s time for accountability

- [Guest essay] At only 26, I’ve seen 4 wars in my home of Gaza

- [Column] Syngman Rhee’s bloody legacy in Jeju

Most viewed articles

- 1[Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- 2[Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- 3Faith in the power of memory: Why these teens carry yellow ribbons for Sewol

- 4Final search of Sewol hull complete, with 5 victims still missing

- 5[Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- 6How Samsung’s promises of cutting-edge tech won US semiconductor grants on par with TSMC

- 7Korea ranks among 10 countries going backward on coal power, report shows

- 8Pres. Park an accomplice in ordering resignation of CJ Group vice chairman

- 9[News analysis] Watershed augmentation of US-Japan alliance to put Korea’s diplomacy to the test

- 10K-pop a major contributor to boom in physical album sales worldwide, says IFPI analyst